Security Incident Response - a Process

by Jeff

A Call for Help

Recently while doom-scrolling Twitter during this pandemic I noticed this cry for help:

I replied with a link to the Security Incident Response template that I’ve used for awhile now and thought it might be good to deep dive into its use.

Incident Response

Key to every security program is having a plan of action for when your team is asked to respond to a security incident. You don’t want to get a 2am (why is it always 2am?) wake up call/text/alarm and start making up a response plan.

Usually efforts to generate response plans start out big and get bigger, attempting to address every potential outcome and cover every aspect of a system response until they amass volume after volume that will eventually sit on a shelf.

“Everybody has a plan until they..”

Your plan is not a process. What do you do for incidents which do not yet have a plan? You need a process.

A Different Approach

I like a more realistic approach that my team and I worked up while I was at Mozilla. Knowing that you cannot predict every potential incident, focus on the process you will use to resolve incidents and ensure that process is self-documenting.

Benefits of a Template

There are many benefits to having a universal template you use for all your security incident response efforts:

- You have some place to start (copy the template)

- You now have a repeatable process (follow the template)

- You are forced to think through the sections (predictable, repeatable)

- You have a place to capture discoveries, thoughts, theories, actions, next steps, lessons learned, evidence, etc.

- You can share the in-process work at any time

- Realtime platforms like Google Docs allow you to bring in selected individuals as needed on whatever device they happen to have handy (phone, laptop, tablet, etc)

Drawbacks of a Template

A template is not exactly a plan. A template doesn’t tell you the specific steps you’d use to respond to a phishing attack or a denial of service. It does however give you a process to use to respond that you can build into a plan for a specific type of incident. Capture the lessons learned from a phishing incident and use those to generate a plan/runbook. Capture the next steps and actions you performed in a denial of service and generate another plan/runbook. Now you are doing incident response and generating plans that by definition are based in reality.

Here’s a Template

While at Mozilla my team responded to many security incidents and in the process worked up a template that served us well. Being open is central to the mission of Mozilla and we published it, but the links have faded over time. Here’s a refreshed copy of the template in Google Docs.

Let me walk you through the sections, but first who uses this?

Incident Commander

I’m a fan of the Pager Duty incident response docs. They make a great call out for there to be a specific incident commander assigned to each incident. While the particulars of the role can vary between organizations (who is one, how are they assigned, is commander the right term) having someone responsible for resolving the incident is key to ensuring it gets resolved and doesn’t linger somewhere in between an investigation and an incident. I believe it’s the role of the incident commander to ensure the template is used and always up to date. Driving incident response from a documentation and process viewpoint ensures the commander role is about accountability and resolution. While all team members should feel free to contribute to the document, it’s the commander’s job to make sure that the document is correct.

Now onto an overview of the sections of the template.

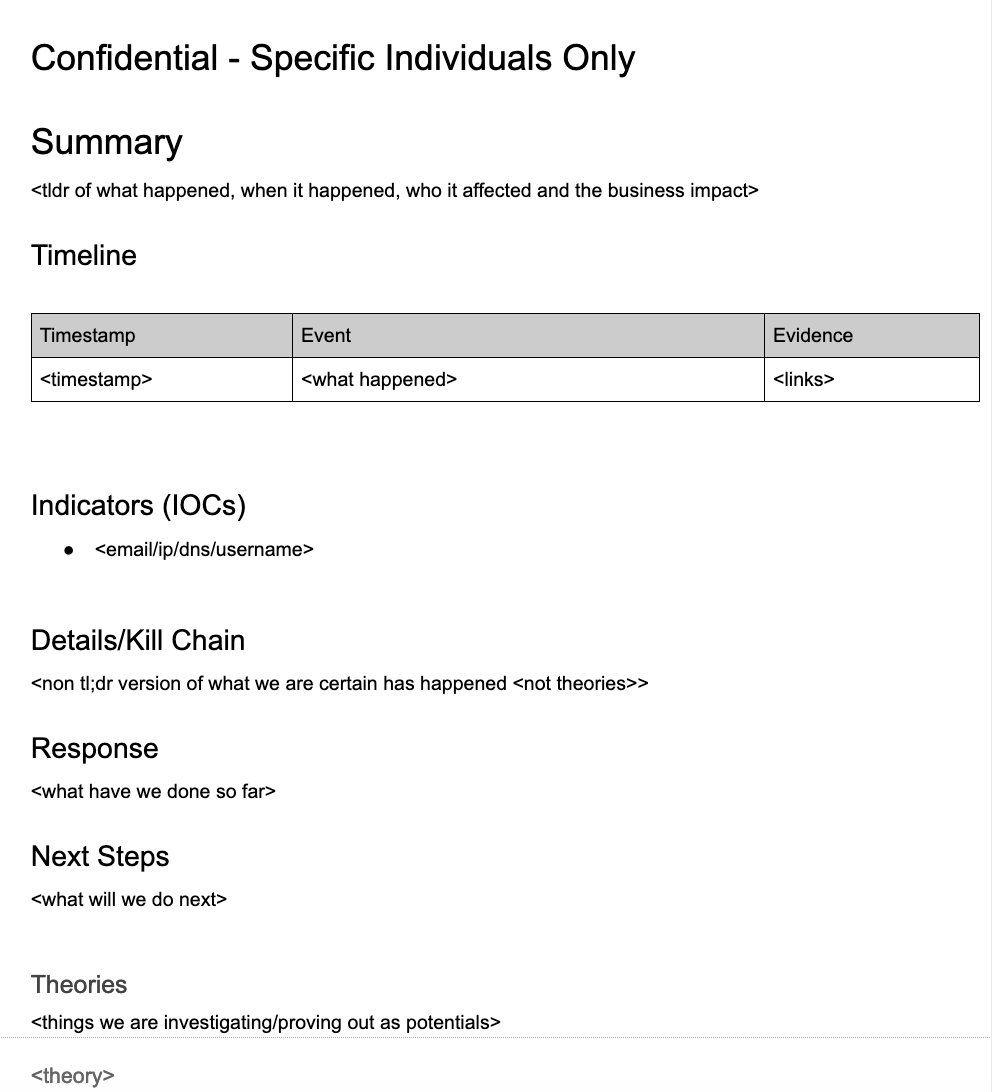

Data Classification

It’s important to settle on a data classification so that folks you bring into the incident will understand how they are expected to treat this information. If you are engaging your counterparts in HR, Finance, Legal, PR, etc who may not be familiar with a classification, be sure to spend time with them so they understand and do not mis-step.

In this case we have used the generic description of ‘Confidential - Specific Individuals Only’ to denote that the resulting document is sensitive and it should only be shared with individuals, rather than groups or an entire company. If your company has an official data classification schema, adjust accordingly.

Summary

This is for future you, and more importantly for your executive audience. Be brief and factual: “On date corporation X was notified that it had suffered an incident type resulting in the business impact”.

You should be able to print this, email it or invite your C-level into the doc at any time and this summary should be viewed as the primary communication to that audience.

Timeline

One of the most important parts of the template. The timeline is your record of what happened and when it happened. It establishes the facts in chronological order and can be essential to solving the mystery of a security incident. Fill it out immediately, use a common time zone and correct it as information arrives so it is always accurate. Use links as a jumping off point to more detailed information about an event.

Indicators (IOCs)

This is meant to be a handy reference for orientation. Simply record who we are talking about (email, IP, DNS, Hostname) such that we have a common understanding without having to resurface elements from log entries, forensic artifacts, etc.

Details/Kill Chain

The exhaustive details of what happened go here in a narrative form. Only include things you know to be true, not theories or a todo list. It’s ok if this is blank at the beginning! Use the Intrusion Kill Chain as a reference for the phases if needed.

Response

This is your opportunity to record what you have done so far. One of the most important sections, keep it up to date with everything you’ve done that has helped resolve the incident.

Next Steps

Did someone say they’d do something? Hold them accountable here. Is there a todo without an assignee? Get someone to volunteer to take on a task/thread in the incident resolution. This and the ‘response’ sections should be the busiest parts of the entire document. I’ve found it extremely useful to engage all the features of Google Docs (mentions, comments, assignments, etc) in these sections to ensure everyone is on the same page about what comes next.

Theories

Often, you don’t know what exactly has happened. You may only know what has resulted. Here’s a place to detail theories you may want to pursue. It’s ok if they are wild theories! It’s a no judgement zone for ideas to flow and a place to capture them when they are fresh.

Lessons Learned

Capture these when they occur, are fresh and raw. Don’t worry about refining them. When the incident is concluded, review them, ensure there is agreement and identify ones that will find a home in a playbook or an initiative. One of the defenders’ only advantages is the opportunity to build a better battlefield for the next round. Don’t lose a chance to improve your odds!

Background

Sometimes in complex situations, there is context that is missing for some folks involved in the incident. Here’s a place to record that context, if needed.

Comms

Communication is key during an incident. Your PR, HR and Legal groups will want to work with you on any internal or external communications. If you don’t collaborate in this section, do at least link to other documents that are created for comms as a reference.

Appendix

Last, but not least a place to put details of logs or screenshots or other miscellaneous items that don’t fit anywhere else or are too detailed. This shouldn’t be terabytes of information, just key extracts that are pertinent to the discussion.

Try it out!

Feel free to copy the template somewhere and give it a whirl the next time you have a security incident to resolve. Let me know how it works for you!

tags: infosec - incident response